Returning to the memoirs of General Griois with a scene from the Russian retreat. Arriving back at the ruined city of Smolensk on 13 November, Griois, after procuring some shelter and food, seeks out Murat to report on the loss of his artillery. He finds him with his wounded chief of staff, Belliard, and is struck by the touching scene.

***

Source: Mémoires du Général Griois, Vol II, pages 123-128.

The 13th of November, we set off again before daybreak. The cold had not yet been so violent; one could not remain on horseback, and the ice on the roads would not have allowed it. So it was on foot and accelerating our march, as fast as our strength permitted it, that around one o’clock in the afternoon we arrived at the summit of a height which dominates Smolensk. Finally we reached it, that town where the army flattered itself it would find, if not the end of its miseries, at least some rest, and a shelter from the cold. We wanted it too badly to doubt it, and without wanting to remind ourselves that three months beforehand we had watched the flames devour this city and had left there only desolation, we hurried there today with confidence, as to the door to our salvation. The idea that the end of our troubles was near gave us a sort of gaiety, and it was while joking about our prolonged slips and frequent falls that my comrades and I descended the mountain and arrived at the surrounding wall. A horse lying in a ditch, the scraps of which several soldiers were fighting over, destroyed or at least reduced to very little the hopes with which we had flattered ourselves. Nevertheless we hastened to cross the bridge and enter the town which, by a happy chance, the gate was then entirely free, and we climbed, not without pain, because of the ice with which it was covered, the steep street which led from this gate to the center of Smolensk.

The Emperor had been there for three or four days and the rest of the army came there in succession. The first arrived had occupied all the houses still upright and down to the smallest sheds. Those who followed, rejected everywhere, had to bivouac in the street or on the squares, without shelter and in a cold of 28 degrees, too happy when they found some morsels of wood to feed the fires they grouped around. We understood easily, in view of this disorder, that we had sought in vain to lodge ourselves into this town. We traversed it as quickly as the difficulties of every kind that stopped us at every step permitted, and we left by the opposite gate. By distancing ourselves from the crowd, we had more chances of finding a cottage, and if it was necessary to bivouac, we would do it as conveniently in the fields as in the street. Fortunately, the artillery of the guard was established on the side where we were going. Our comrades came to our aid and ceded to our little caravan a sort of half-covered shed, occupied by their horses, which they withdrew. For us this was a veritable palace, where we established ourselves with our men and our horses. After this I went to the bivouac of Colonel Boulart, chef de bataillon in the guard, who invited me to sup with him. He was under a tent, and I made a meal I will never forget in my life: wine, bread, meat, coffee, all things I had long since lost the habit of. So I did honor to it, despite the extreme cold, which was such that we had to break our wine with a hatchet and put it on the fire. It was late night; after amply restoring myself, I left Boulart who had to depart the next morning, and I regained our shed where I found such an abundance of provisions, which is to say flour, salt and a little brandy that our men had procured, at the risk of being suffocated, by entering the stores with the crowd. It was for us a day of feasting, and, without having made as good a supper as me, my comrades had shared the meal of some friends in the guard.

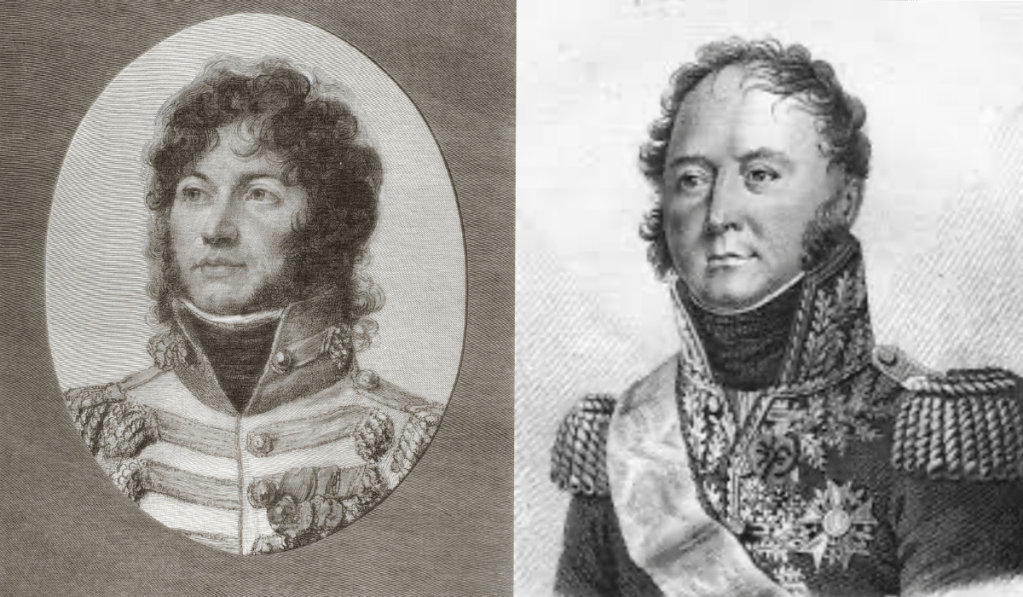

As I have said, it was without orders or rather for lack of orders that I had followed the 4thCorps to Dorogobuzh. It was my duty to report to the King of Naples, commanding the army’s cavalry, and my first concern in Smolensk was to look for the lodging of General Belliard, Murat’s chief of staff. I was doing this for the sake of my conscience: the complete disorganization of the cavalry rendered my report useless. It was quite an immense building, destroyed by the flames before even being finished; yet a small stairway still survived. I climbed it without encountering either servants or orderlies; I pushed a half-broken door; I spotted Murat and Belliard chatting happily. Belliard, still suffering from the wound he’d received at Mojaïsk, was lying down on a bad pallet, on which Murat occupied a part, sitting at his feet. The picture was not without interest. A king, because after all he was one and was recognized as such, keeping company with one of his wounded generals and appearing as a friend caring for another friend, it is a rare thing, and I confess I was touched by it. But I had by no means expected to find King Murat there; the news I brought of the loss of my artillery was neither agreeable to tell, nor to hear, and besides no longer had any importance; I withdrew without being noticed. Murat contented himself with asking who was there; I did not respond, and did not see Belliard again until six weeks later, at Elbing.

After staying some time at our bivouac on returning from Colonel Boulart’s, I headed towards the town to look for Prince Eugène, who I had not seen since morning and from whom I had, as usual, to take orders for the next day. The darkness of the night and the frightful mob that filled Smolensk did not make the thing easy. However, I arrived at the house where his headquarters was established. I did not find him there; he was, I was told, with the Emperor. I went to the Emperor’s; impossible to see the prince, he was in Napoleon’s chamber. The meeting was long; it seemed to me all the more so because the room in which I waited was oriented towards all the winds and it was freezing cold, despite the fire the officers maintained with care. At last the door opened, Eugène appeared and Murat with him.

Murat seemed very cheerful, and from his noisy outbursts, one would not have divined our sad position. Eugène left him to come to me: “My dear Griois,” he told me, “find yourself before daylight on the road by which we came today. I will go there too. Broussier’s division, which I left in position there, is surrounded by the enemy; it must be freed. See you tomorrow then.” He left me thereupon, and I, frozen with cold and very annoyed at this order, returned to our hangar and woke Colonel Berthier, my chief of staff, who in that capacity was to accompany me.

***

[Other excerpts from Griois’ memoirs can be found here and here.]